A natural question when people hear about Kivy as a way to create Android apps in Python

is…what can you do with it? Is it performant enough for games, can

you call the Android APIs, do all apps look the same? One of the best

resources for these kinds of question are existing apps, and in this

post I’ll give a quick impression of three of my favourites. This is

obviously highly subjective, but I’m focusing in particular on

features of technical interest, apps that push Kivy beyond what’s

normal to show what it is capable of.

If you’re interested in other examples, there’s a fairly extensive

(but far from exhaustive) list on the Kivy wiki,

including winners of our programming contests and many contributions

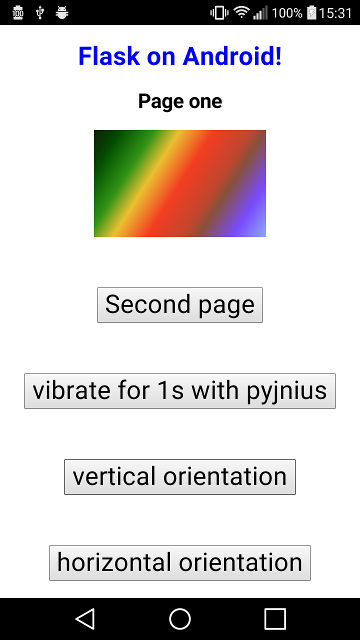

from users. If you’d like to make your own apps in Python, check out Kivy (which also runs on Windows, Linux, OS X

and iOS) and python-for-android (which can

also package non-Kivy Python apps).

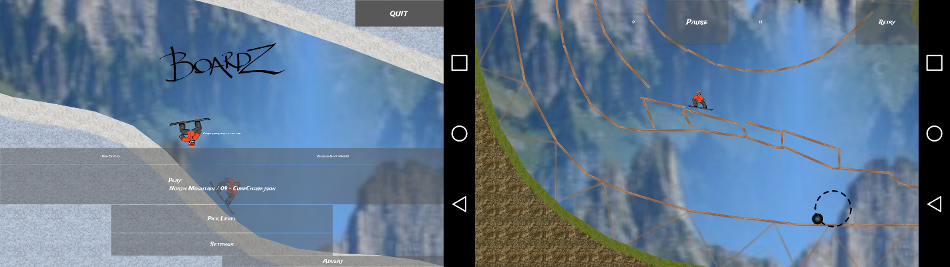

Boardz

You can download Boardz here.

I’ve put Boardz first because it’s my single favourite Kivy app. It’s

actually a work in progress (and in fact hasn’t been updated for a

while), but is already a fun game showcasing some of Kivy’s more

impressive performance potential.

Boardz is a snowboarding physics game; you control your snowboarder by

touching the screen, then moving your finger with respect to its

initial position to control your posture; quick movements

throw your weight around and can cause you to jump, spin, or fall

over, while just positioning the rider differently helps you to pick

up speed or navigate barriers. The objective of the game is to get to

the end of each stage, with different obstacles including

slopes and jumps, collapsing structures, falling rocks, or even

multidirectional gravity and rocket boosters. You can fail if your

head collides with another object with too much force, or if you

simply get stuck and can no longer reach the finish.

What’s immediately impressive is that all this runs well as a Python

powered game running on a smartphone. It achieves this by being built

using the KivEnt game engine developed by

Jacob Kovac, one of Kivy’s core developers. This entity based system

lets you write game code in Python but internally is highly optimised

in Cython, using Kivy’s OpenGL API extremely efficently as well as

interfacing with the popular Chipmunk Physics engine.

Boardz betrays its in-progress nature in other ways; you can see in

the above screenshots that its UI isn’t very polished, and in this

sense it’s the worst of the apps I’m showing here. However, it makes

up for this with its surprisingly engaging gameplay, and a breadth of

entertaining features not showcased here, including leader boards,

racing your ghost, and different riders with different physics attributes.

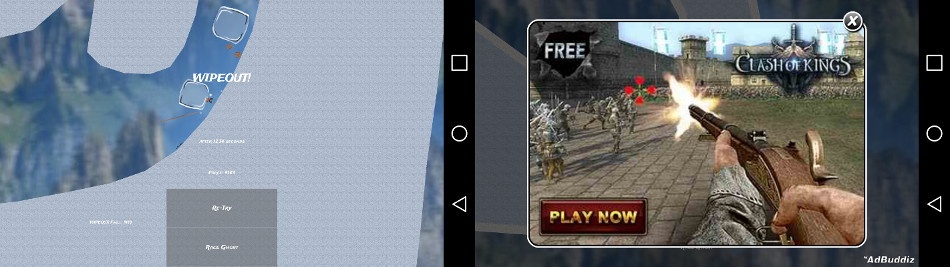

A final technical feature interesting to Kivy app developers is that

Boardz includes ad integration. Regardless of your feelings about ads

themselves, the ability to use them is a major feature enquiry from

new Kivy users. The problem here is that integrating with a normal ad

provider normally requires adding to the Java components of your app,

which it may not be immediately obvious how to do from Python. There

are actually a number of resources for this nowadays, with a key point

being that python-for-android tries to make

it easy to include extra Java code, with which you can interact from

Python using Pyjnius. KivEnt’s

implementation, pictured above, is a nice demonstration.

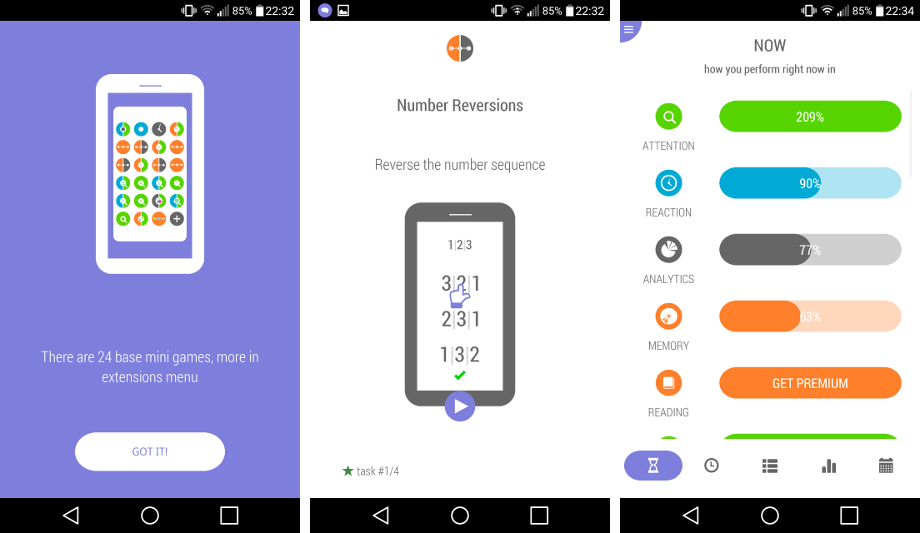

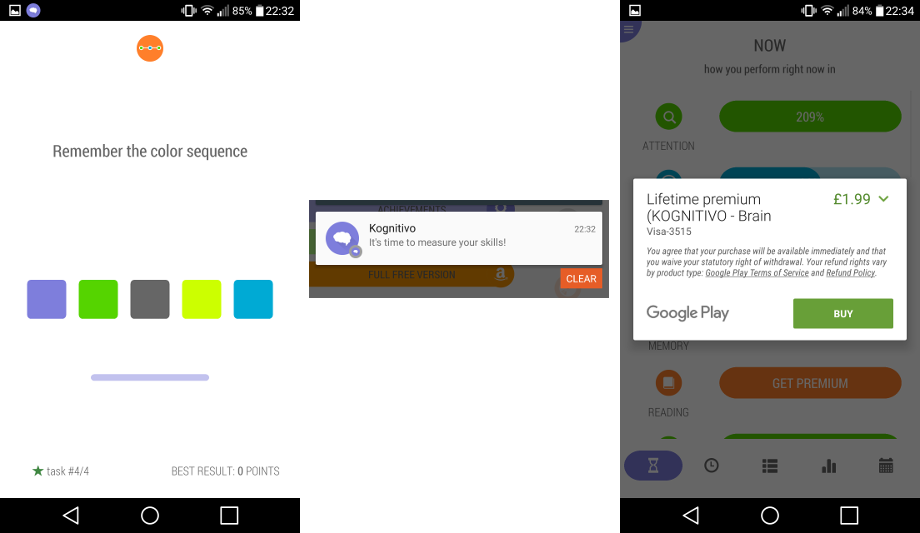

Kognitivo

You can download Kognitivo here.

Kognitivo is perhaps the single most polished Kivy app on the Play

store, being relatively complex, extensively customised, and

exhibiting a number of nice Android API interactions. It is also

(deservedly) possibly the most popular Kivy app on Google Play.

Kognitivo is a brain training and performance monitoring app. The

basic structure is to perform a series of simple exercises intended to

test different aspects of cognitive performance, being rated on

accuracy and speed, and with the results compiled over time in order

to detect and act on trends.

As I’ve said already, the nice thing about Kognitivo is its huge amount

of polish. It is extensively themed such that no trace of the Kivy

defaults remains, runs extremly smoothly, and includes many nice

animation tweaks (unfortunately not captured in screenshots) to feel

responsive and active.

On the technical side, Kognitivo exhibits a number of features not

normally included in Kivy applications but possible through

interaction with the Android API via some Java code and/or the

aforementioned Pyjnius. These include notifications, interaction with

your calendar, and in-app purchases.

The author of Kognitivo, Sergey Cheparev, has his own writeup of

Kognitivo’s development on his blog, including

discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of Kivy development,

and of the experience of putting together all these features. This is

a great resource on its own; I don’t agree with some of the author’s

criticisms and some of Kivy’s features have been improved since then,

but it’s an excellent overview of the experience. Most of all, he

enthusiastically captures some of my own reasons for finding Python on

Android interesting:

I think the most beautiful thing in it is to use the almightiness

of [Python]’s frameworks. I used sqlalchemy and sqlite as a

backend, and it worked like a charm! Python is the most powerfull

language because of it’s frameworks, you can even start Django on

your smartphone! It’s amazing! Or twisted for asynchro

communication with server. Or nltk for in-app natural language

processing. Or maybe you want make a mobile equations solver with

scipy and numpy. This makes all the dreams come true.

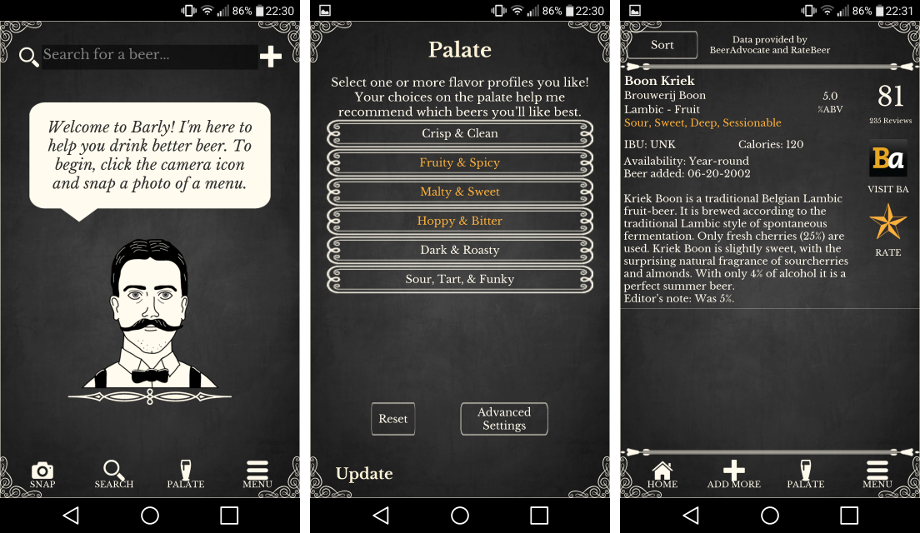

Barly

You can download Barly here,

or visit its own website.

Barly is the most recent of these apps to appear on Google Play. I’ve

chosen to include it as a nice example of pulling off its concept

quite well while making good use of Kivy; like Kognitivo the app is

themed very differently to Kivy’s defaults (though it doesn’t look

like a normal Android app either), and is generally well put together.

To quote its Google Play blurb, Barly is ‘your personal beer

expert’. It provides a convenient interface to browse beers via data

from standard popular websites, and according to your description of

your own palate. Barly’s most interesting feature is the ability to

take a picture of a beer menu and have it automatically detect what

beers are listed, followed by downloading information about them to

help you choose. That kind of image analysis has to be tricky, but

actually didn’t perform badly when I tested it.

The interface to this functionality is quite nice, switching to the

Android camera app to get the image before uploading it to a server

for processing (during which you can input your preferences). This

functionality is possible with Pyjnius as mentioned previously, but

actually in this case is an API also exposed in pure Python by Plyer (another Kivy sister project,

wrapping platform-specific APIs in a Python frontend). Not all APIs

can be conveniently exposed this way, and actually Barly may not even

be using this particular method, but it’s a good example of

functionality that can be achieved with Kivy in a particularly

cross-platform way.

Beyond this, Barly does not make such wide use of the Android API or

unusual Kivy features, but nor does it try to; it is a nice example of

a complete and self-contained Kivy app using the power of Python for

an unusual and interesting goal.